Influenza is hitting the United States unusually early and hard, resulting in the most hospitalizations at this point in the season in more than a decade and underscoring the potential for a perilous winter of respiratory viruses, according to federal health data released Friday.

While flu season is usually between October and May, peaking in December and January, it’s arrived about six weeks earlier this year with uncharacteristically high illness. There have already been at least 880,000 cases of influenza illness, 6,900 hospitalizations and 360 flu-related deaths nationally, including one child, according to estimates released Friday by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Not since the 2009 H1N1 swine flu pandemic has there been such a high burden of flu, a metric the CDC uses to estimate a season’s severity based on laboratory-confirmed cases, doctor visits, hospitalizations and deaths.

“It’s unusual, but we’re coming out of an unusual covid pandemic that has really affected influenza and other respiratory viruses that are circulating,” said Lynnette Brammer, an epidemiologist who heads the CDC’s domestic influenza surveillance team.

Activity is high in the U.S. south and southeast, and is starting to move up the Atlantic coast.

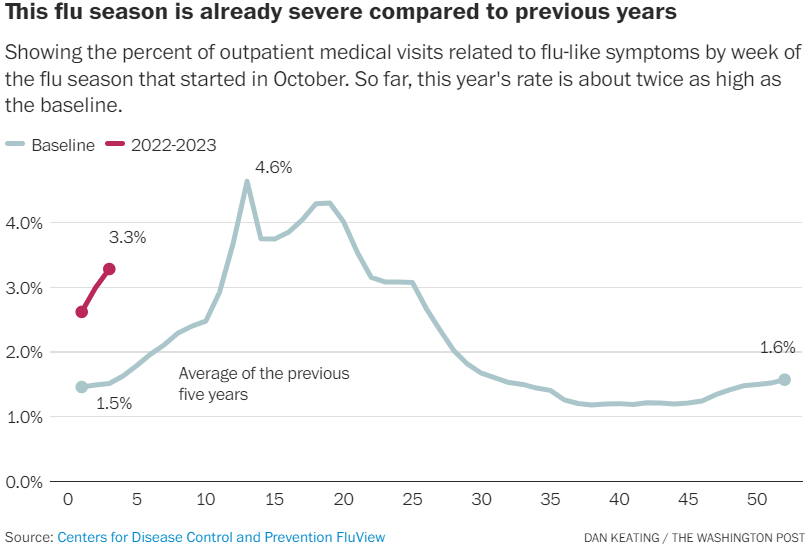

The CDC uses a variety of measures to track the flu, including estimating the percentage of doctor visits for flu-like illness. But given the similar symptoms that could include people seeking care for covid-19 or RSV, another respiratory virus with similar symptoms, the laboratory data leaves no doubt.

“The data are ominous,” said William Schaffner, medical director for the nonprofit National Foundation for Infectious Diseases and a professor of infectious diseases at the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine. “Not only is flu early, it also looks very severe. This is not just a preview of coming attractions. We’re already starting to see this movie. I would call it a scary movie.”

Adding to his concern, he said, is that influenza vaccination is lagging behind where it usually is at this point in the season. About 128 million doses of flu vaccine have been distributed so far, compared with 139 million at this point last year and 154 million the year before, according to the CDC.

“That makes me doubly worried,” Schaffner said. The high burden of the flu “certainly looks like the start of what could be the worst flu season in 13 years.”

The number of flu cases this season is already one-eighth of last season’s total estimate of 8 to 13 million cases.

The latest flu data comes as the nation’s strained public health system is grappling with multiple virus threats. Coronavirus cases are expected to increase as the country heads into colder weather and more people gather indoors. New covid-19 subvariants with greater ability to dodge immune defenses now account for 27 percent of cases, up from 17 percent a week ago. Children’s hospitals are filling up with a record number of kids infected with RSV.

The flu vaccine’s effectiveness in preventing a doctor visit, hospitalization or death is uneven from year to year, and in years past, has hovered between 40 and 60 percent, according to the CDC. But Brammer and others say this season’s vaccine is well matched against circulating strains. That offers a “little ray of sunshine” for what could be a bleak winter, Schaffner said.

Nationally, the predominant virus — a particularly nasty strain, H3N2 — causes the worst outbreaks of the two types of influenza A viruses and two influenza B viruses that circulate among people. Seasons where H3N2 dominate typically result in the most complications, especially for the very young, the elderly and people with certain chronic health conditions, experts say.

What many people don’t realize is that even after someone recovers from the flu, the inflammatory response generated by the virus continues to wreak havoc for another four to six weeks in those who are middle-aged and older, increasing the rate of heart attacks and strokes, Schaffner said.

Influenza has not been a serious problem the last two years, experts and health officials have said, because of the masking, social distancing and other measures people took to protect themselves against covid-19.

Health officials tend to consider a flu season to be officially underway after consecutive weeks of flu activity from several surveillance systems, including a significant percentage of doctor’s office visits for flu-like illnesses. Those doctor visits have increased for three weeks in a row as of Oct. 22, more than a month earlier than previous seasons, the CDC’s Brammer said.

The flu is famously difficult to predict. It’s hard to know how long the season will last, how severe it might be, and if different parts of the country will experience different levels of respiratory disease at different times. Last season, flu activity peaked in January, “then dropped like a stone, then smoldered just under the epidemic threshold beyond March into April, May and June,” said Schaffner. That “long smoldering tail was very unusual.”

“An early start doesn’t always mean severe,” Brammer said.

In the Southern Hemisphere, influenza season has also been far different, Brammer said. In Australia, there was a “really sharp, very fast uptake then very quick drop,” she said. In Argentina, the peak flu activity occurred at what would have been that country’s summer.

“Things have not settled back into a normal pattern,” Brammer said.

Chile got ahead of its bad flu season, which began months earlier than a typical season, by rapidly vaccinating 88 percent of its high-risk population before peak influenza activity, according to a CDC report this week. The flu vaccine used in Chile, which included a match for the dominant H3N2 virus, was about 50 percent effective in preventing hospitalization. The shot used in the Northern Hemisphere includes the same virus makeup as the Southern Hemisphere vaccine, so experts hope the formulation might be similarly effective in preventing severe influenza illnesses.

The latest CDC data shows overall respiratory illness activity is “very high” in South Carolina and D.C., and “high” in 11 states: Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, New Jersey, New York City, North Carolina, Tennessee, Texas and Virginia.

Texas was among the earliest states to see flu activity in late September. At the Houston Methodist hospital system, laboratory-confirmed influenza cases have risen to 975 as of Oct. 20, up from 561 the week before, officials said.

Officials had been bracing for a more robust flu season this fall and winter because so many people have dropped covid protection measures and are reluctant to get vaccinated.

“This was something that we were expecting because we are a hub, and a lot of people are traveling here,” said Cesar Arias, the hospital system’s chief of infectious diseases. But, he said, “I didn’t expect to see that much [flu] that early.”

Arias said conversations around flu vaccinations have become tied to the hesitancy around coronavirus vaccines. The conversations in Texas, “as you can imagine, [are] stronger and at least more vocal,” he said. “We are struggling with that, trying to put the message out to get vaccinated.”

People need to get a new flu vaccine every year to be protected, and it takes up to two weeks for protection to kick in and for the vaccine to work. Flu is contagious before symptoms start. The CDC recommends that everyone ages 6 months and older get a flu vaccine, ideally by the end of October.

Recent Comments